In addition to being used in clinical environments, ventilators can also support patients in home and care settings.

What is Ventilatory Support?

Ventilatory support is a life-saving intervention taken when a patient is unable to facilitate their own breathing due to low oxygen levels, severe shortness of breath or other causes of respiratory distress (ATS 2020).

Ventilation takes over the work of breathing by delivering oxygen into the lungs, reducing the level of effort required by the patient (ATS 2020).

A patient can receive ventilatory support in a number of ways:

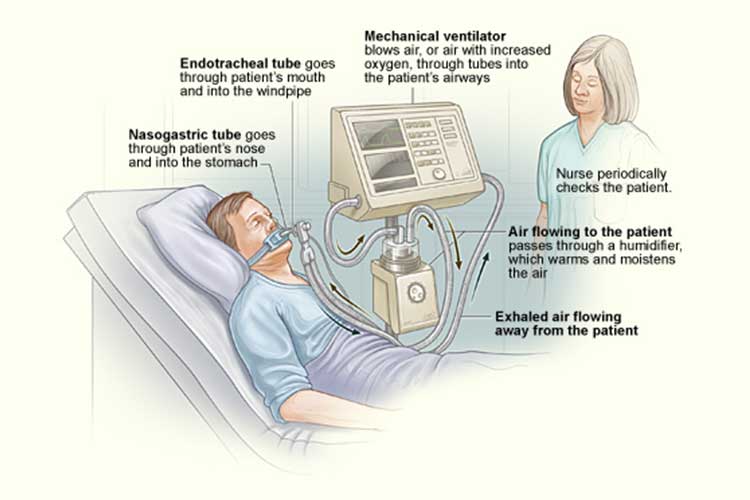

- Mechanical ventilation is invasive and involves the insertion of an endotracheal tube through the patient’s mouth or nose into the trachea. This tube is connected to a mechanical ventilator, a machine that moves air in and out of the patient’s lungs.

- Non-invasive ventilation is the provision of ventilatory support through an external interface (mask or helmet). Intubation is not required.

- Patients with a tracheostomy may receive ventilatory support through mechanical ventilation.

(NHLBI 2022; Nickson 2019; NDIS 2022)

What is a Ventilator?

A ventilator is a machine that supports a patient’s breathing. It delivers moist, warm, oxygen-rich air through either an endotracheal tube or interface (depending on whether the ventilatory support is invasive or non-invasive) and into the patient’s lungs using positive pressure. The patient will either exhale on their own or the ventilator will do so for them, depending on their condition (idsMED 2019; Elsevier 2019).

The ventilator will assist the patient to intake and expel adequate amounts of oxygen and carbon dioxide respectively. The amount of oxygen delivered to the patient, as well as the size and frequency of each breath, depends on how the patient normally breathes and can be controlled by staff through the ventilator’s monitor (idsMED 2019; Elsevier 2019).

Using a ventilator will reduce the energy and work of breathing required by the patient to breathe (idsMED 2019).

Mechanical ventilation is complex and requires advanced specialist training, however, there are four basic functions:

- Delivering oxygen (fraction of inspired oxygen: FiO2)

- Setting a respiratory rate if the patient is unable to breathe on their own

- Augmentation of each breath

- Providing positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP).

(Williams & Sharma 2022)

Home Ventilation

In addition to being used in clinical settings, ventilatory support may also be provided in a patient’s home or another care setting (e.g. residential aged care) if the patient is experiencing chronic respiratory impairment. Home ventilation can be either mechanical or non-invasive (Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust 2021).

Conditions that may require home ventilation include, but are not limited to:

- Chronic respiratory failure

- Conditions causing impaired respiratory control

- Central alveolar hypoventilation

- Neuromuscular diseases

- Spinal cord injury

- Nerve or muscle disease (e.g. muscular dystrophy)

- Diaphragm paralysis

- Chest wall diseases

- Kyphoscoliosis

- Thoracoplasty

- Pulmonary diseases

- Guillain Barré syndrome

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Cystic fibrosis

- Bronchiectasis

- Lung transplant

- Ventilator dependency.

(Intensive Care At Home 2021)

There is evidence suggesting the prevalence of home ventilation has been greatly increasing for patients experiencing neuromuscular conditions, parenchymal lung disease, sleep-disordered breathing and chest wall deformities (Dale et al. 2017).

As patients requiring prolonged ventilatory support comprise a significant portion of acute care service users, there is a need for a well-timed and optimised transition process from acute care to the home (Dale et al. 2017).

What Are the Benefits of Home Ventilation?

- Allows patients with chronic respiratory illness to live in the community with greater autonomy

- Small, portable ventilators are available, enabling patients to be more mobile and independent while receiving ventilatory support

- Prolongs patient survival

- Decreases hospitalisation

- Reduces the burden of symptoms

- Enhances the patient’s health-related quality of life.

(Dale et al. 2017)

Essential Care Principles of Ventilation

Caring for a patient receiving ventilatory support may involve:

- Communicating effectively with the patient and other members of the care team

- Checking the ventilator settings and identifying any changes in the patient’s condition

- Responding appropriately to ventilator alarms and determining what they mean

- Checking the bag valve

- Conducting appropriate emergency equipment and regular equipment checks

- Suctioning the patient

- Checking the position of the endotracheal tube (in intubated patients)

- Assessing the patient for pain or anxiety and providing appropriate sedation

- Ensuring the patient is haemodynamically stable

- Ensuring there is a backup plan in the event of ventilator failure

- Airway management

- Maintaining all necessary documentation

- Providing education to the patient’s family and allowing them to passively contribute to care (e.g. holding the patient’s hand, speaking to the patient).

(Williams & Sharma 2022)

Caring for a Patient Using a Ventilator in the Home

Note: Always refer to your facility’s policies and procedures.

- Adhere to standard precautions for infection control.

- Don PPE if required.

- Explain the procedure to the patient.

- Review the ventilator type and settings to ensure they adhere to the physician’s orders.

- Ensure the connections and tubing are intact.

- Assess the patient’s lungs.

- Suction if required.

- Perform routine tracheostomy care if applicable.

- Check humidification.

- Ensure the tubing is free from condensation.

- Monitor and record the level of oxygen in the tank.

- Ensure the back of ventilator and spare batteries are present and working correctly.

- Check and test alarms.

- Assess the patient’s gastrointestinal status.

- Assess the patient’s cardiovascular status.

- Assess the patient’s fluid balance.

- Assess the patient’s nutritional status.

- Check for signs of infection (take the patient’s temperature, check for increases in heart rate, check for changes in tracheal secretions).

- Identify and establish methods of communication with the patient.

- Ensure the patient is getting adequate sleep and rest.

- Implement day and night routine.

- Review the patient’s care plan periodically.

- Assess the psychosocial health of the patient and their loved ones regularly. Provide support if required.

- Clean the ventilator equipment.

- Reassemble the equipment.

- Discard soiled supplies as per protocol.

- Update relevant documentation.

(Primecare Network 2018)

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

It’s important to note that intubated patients are at risk of developing ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). Strategies to decrease the likelihood of VAP include:

- Maintaining a bed elevation of 30 to 45 degrees if possible

- Assessing the patient’s need for mechanical ventilation daily, as the risk of VAP increases the longer the patient is intubated

- Maintaining the patient’s oral cavity hygiene if possible

- Encouraging the patient to sit up if possible, as this improves lung compliance and gas exchange

- Providing enteral nutrition if possible, as adequate nutrition will improve the immune system

- Suctioning visible secretions

- Practising aseptic technique (adhere to your facility’s protocol).

(Williams & Sharma 2022)

Other Complications of Ventilation

In addition to VAP, mechanical ventilation is associated with other complications, including:

- Barotraumna (alevolar rupture e.g. pneumothorax)

- Haemodynamic instability

- Volutrauma (ventilator-associated lung injury)

- AutoPEEP (hyperinflation of the lungs)

- Sinusitis

- Laryngeal injury

- Tracheal stenosis

- Tracheoesophageal fistula

- Loss of electrical power to the ventilator.

(Furesz 2017)

Less severe complications of home ventilation may include:

- Wind or distended abdomen

- Facial sores from NIV interface

- Eye soreness from NIV interface air leakage

- Dry mouth

- Nasal irrigation or congestion.

(Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust 2021)

Conclusion

In order to facilitate safe home ventilation and decrease the risk of complications, it is essential to thoroughly monitor and care for patients.

Note: This article is intended as a refresher and should not replace best-practice care. Always refer to your organisation’s policy on home ventilation.

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

True or false: The risk of developing ventilator-associated pneumonia is linked to the duration of intubation.

Topics

References

- American Thoracic Society 2020, Mechanical Ventilation, American Thoracic Society, viewed 20 June 2023, https://www.thoracic.org/patients/patient-resources/resources/mechanical-ventilation.pdf

- Dale, C M et al. 2017, ‘Transitions to Home Mechanical Ventilation. The Experiences of Canadian Ventilator-assisted Adults and Their Family Caregivers’, Annals of the American Thoracic Society, vol. 15, no. 3, viewed 20 June 2023, https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201708-663OC

- Elsevier 2019, Ventilator, Adult, Elsevier, viewed 20 June 2023, https://www.elsevier.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/999003/Ventilator,-Adult_300119.pdf

- Furesz, S 2017, Complications of Mechanical Ventilation, Cancer Therapy Advisor, viewed 20 June 2023, https://www.cancertherapyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/hospital-medicine/complications-of-mechanical-ventilation/

- Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust 2021, Non-invasive Ventilation at Home, National Health Service, viewed 20 June 2023, https://www.hey.nhs.uk/patient-leaflet/home-ventilation-information-for-patients/

- idsMED 2019, ‘How Does A Ventilator Work?’, idsMED, 23 January, viewed 20 June 2020, https://www.idsmed.com/hk-en/news/how-does-a-ventilator-work_398.html

- Intensive Care at Home 2021, Mechanical Home Ventilation Guidelines, Intensive Care at Home, viewed 20 June 2023, https://intensivecareathome.com/mechanical-home-ventilation-guidelines/

- National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute 2020, Ventilator/Ventilator Support, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, viewed 20 June 2023, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/ventilatorventilator-support

- NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission 2022, NDIS Practice Standards: Skills Descriptors, Australian Goverment, viewed 20 June 2023, https://www.ndiscommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-12/Revised%20High%20Intensity%20Support%20Skills%20Descriptors.pdf

- Nickson, C 2019, Non-Invasive Ventilation (NIV), Life in the Fast Lane, viewed 20 June 2023, https://litfl.com/non-invasive-ventilation-niv/

- Primecare Network 2018, Respiratory: Nursing Management of the Ventilator-Dependent Patient In The Home, Primecare Network, viewed 20 June 2023, https://primecarenetworkinc.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Nursing-Policies-and-Procedures.pdf

- Williams, L M & Sharma, S 2022, ‘Ventilator Safety’, StatPearls, viewed 20 June 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526044/

New

New