The Cost of Losing New Nurses

Too many early-career nurses (ECNs) are leaving the profession far too soon. Data shows that nearly 1 in 5 nurses have left their jobs within the first year after graduation. Some leave healthcare altogether. Even by year three, a worrying number have stepped away. Across the broader health workforce, less than 40% expect to stay in their current field five years on.

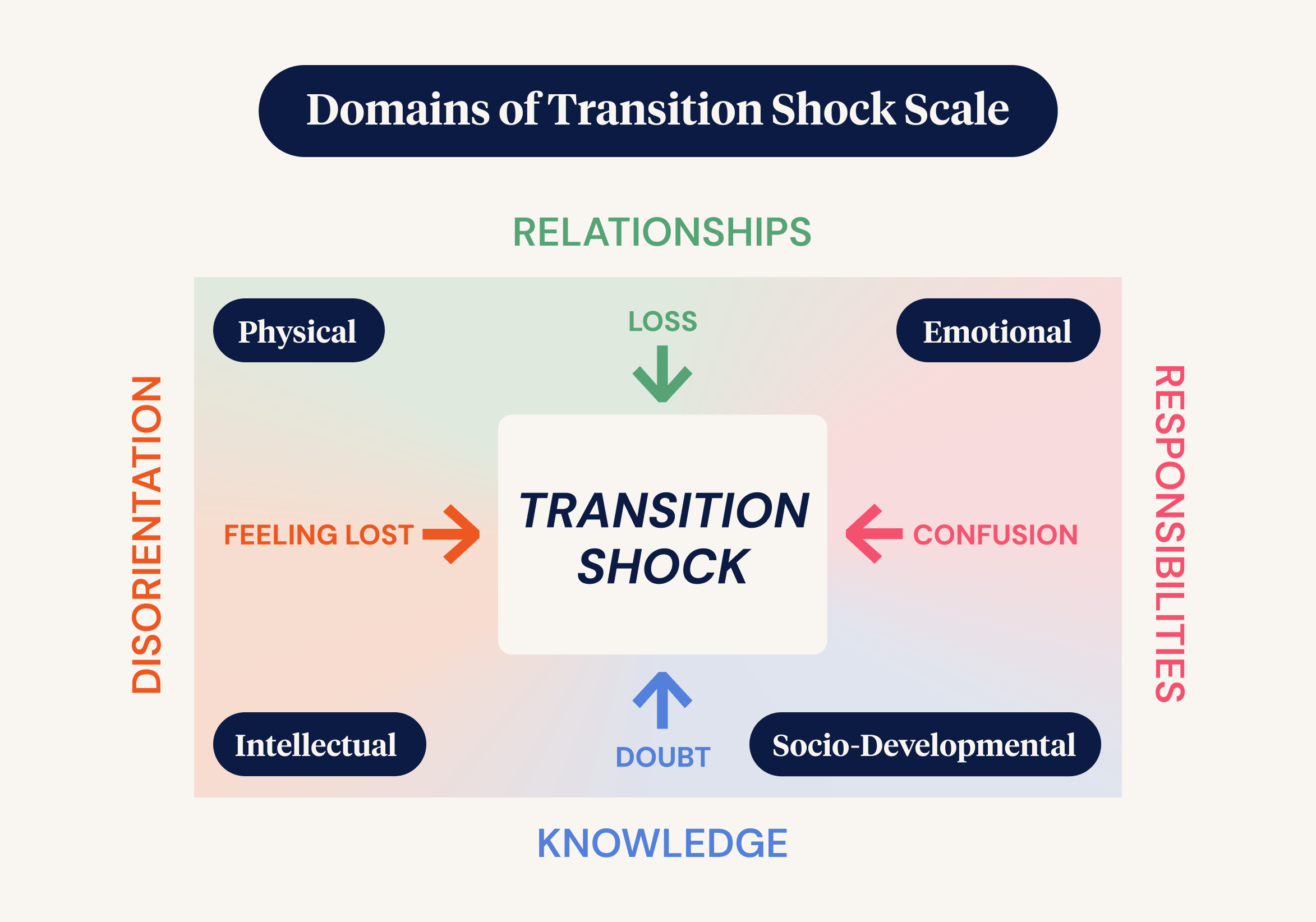

This speaks to a deeper issue—one that’s often overlooked: transition shock. Transition shock is the jolt new nurses feel when the reality of the job doesn’t match what they imagined. It's confusing and stressful and can quickly lead to burnout or disengagement if organisations don't step in with support.

In this article, we unpack transition shock, why it matters, and what leaders can do to ease the journey for ECNs and keep them confident, competent, and committed.

What is Transition Shock?

Transition shock occurs when nursing graduates take their first steps into the workforce and suddenly realise just how different real-world practice is from the classroom. The shift can feel like being dropped in the deep end—fast-paced shifts, complex patients, team dynamics, and big responsibilities hit all at once. Many new nurses feel out of their depth.

This shift impacts them across five key areas:

- Emotional - Fear, anxiety, and self-doubt are common, significantly when confidence outpaces experience.

- Physical - Long shifts, rotating rosters, and physical fatigue take a toll.

- Intellectual - There’s a steep learning curve. Theoretical knowledge must be applied in fast, unpredictable clinical situations.

- Sociocultural - Team dynamics and unwritten workplace norms can leave new nurses feeling excluded or unsure how to fit in.

- Developmental - At the same time, they’re building their identity as nurses and learning what kind of professionals they want to be.

Canadian nursing scholar Judy Duchscher describes this first year in three stages:

- Doing (0–3 months): Nurses focus on getting through the day, relying heavily on guidance and routines.

- Being (4–6 months): They start to reflect more, ask deeper questions, and notice gaps in the culture and systems around them.

- Knowing (7–12 months): They begin to define who they are as professionals, seeking meaning in their work. But if reality falls short of expectations, disillusionment can set in.

What Organisations Get Right — and Wrong

Leaders play a key role in shaping this early experience. Below are five areas that can either support or undermine an ECN’s transition:

1. Poor Orientation

Generic, one-size-fits-all orientation just doesn’t cut it. New nurses need a tailored, welcoming program that introduces them to the culture, sets clear expectations, and gradually builds their skills and confidence.

2. Inconsistent Preceptorship

Preceptors — experienced nurses who mentor new staff — are crucial. But when support is inconsistent or rushed, it becomes a missed opportunity. Graduates benefit most from committed preceptors who are well-prepared, available, and genuinely invested in their growth.

3. Workforce Pressures

Short staffing, heavy patient loads, and skill mix issues make it hard for new nurses to thrive. They need some breathing room — protected workloads, thoughtful rostering, and support as they build their capability.

4. Culture and Team Dynamics

Unspoken rules, lack of feedback, or a “sink or swim” culture create stress. ECNs must be guided into team life, coached on communication and non-technical skills, and offered safe ways to ask questions or raise concerns.

5. Lack of Role Clarity

Many new nurses feel they’re left to figure things out alone. Clear expectations, scenario-based learning, and extra time in supernumerary roles can help build judgement and confidence before full independence.

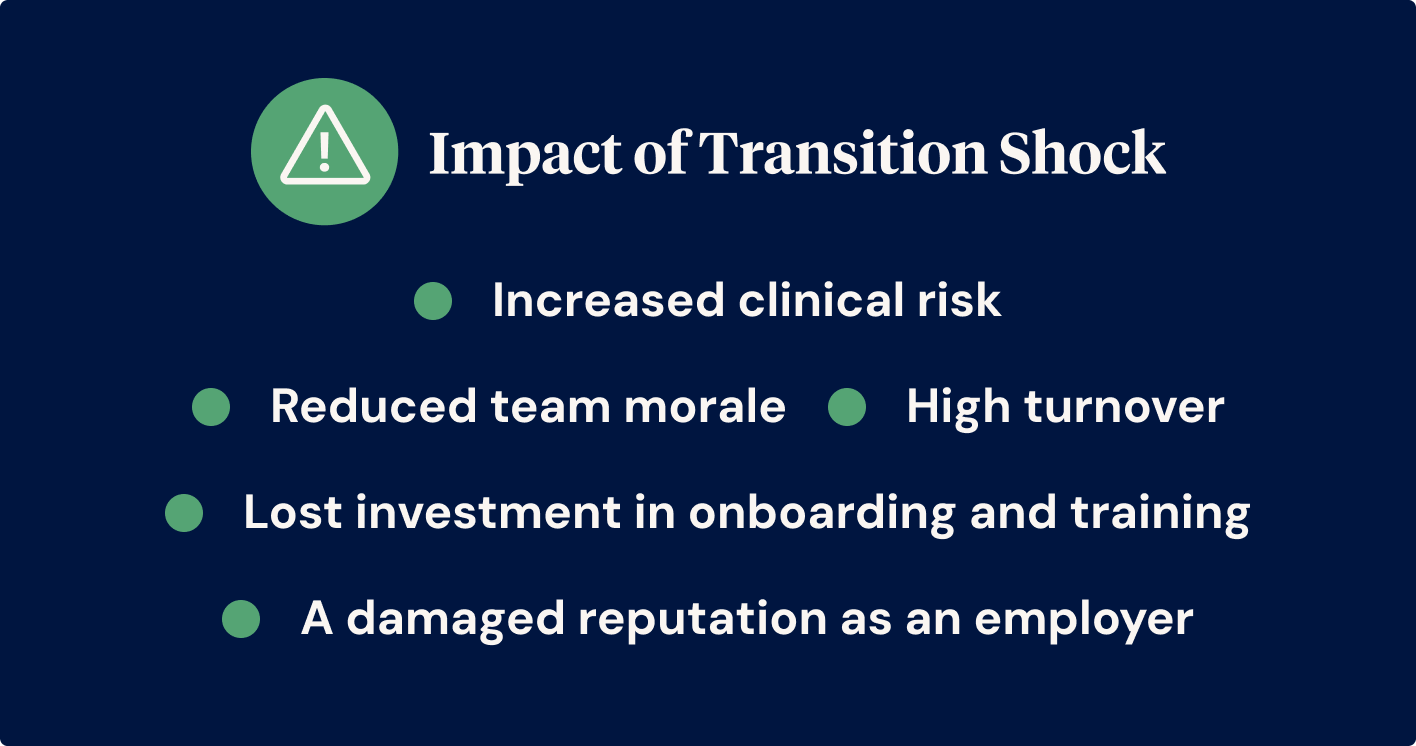

The Cost of Doing Nothing

When transition shock isn’t managed, the consequences are real:

- High turnover

- Reduced team morale

- Increased clinical risk

- Lost investment in onboarding and training

- A damaged reputation as an employer

It’s not just the individual who suffers — the whole organisation feels the impact.

Supporting New Nurses

Good leadership can make all the difference. Here are some key strategies:

1. Invest in Deeper Transition Programs

Move beyond the basics. Include real-world scenarios, peer shadowing, and staged responsibility. Give graduates time to find their feet before expecting full independence.

2. Build Stronger Preceptorship

Train and support your preceptors. Recognise their contribution and give them the time they need to mentor well.

3. Foster Psychological Safety

Create a culture where questions and mistakes are treated as learning opportunities. Regular check-ins and supportive feedback help new nurses feel seen and valued.

4. Encourage Peer Support

Make space for peer debriefs, reflection, and emotional processing. Transition can be lonely — connection makes it easier.

5. Monitor and Adapt

Use workforce data, exit interviews, and team feedback to spot issues early. Adjust programs as needed. Leaders who act on what they see build trust and improve retention.

Supporting early-career nurses through transition is more than a nice gesture. It’s a workforce sustainability strategy. The first year of practice sets the tone for long-term engagement, performance, and retention. Done well, it benefits staff, patients, and the organisation as a whole.