What is Hypoglycaemia?

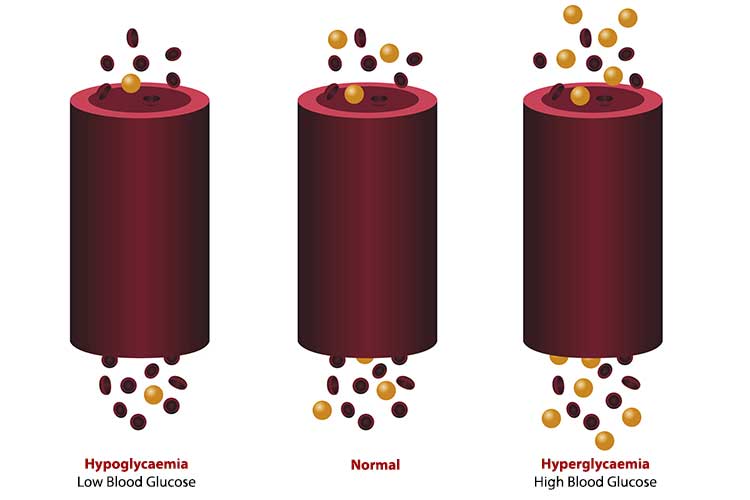

Hypoglycaemia occurs when a person’s blood glucose level (BGL) drops to a very low level (below 4 mmol/L) (Diabetes Australia 2024).

How Does the Body Respond to Hypoglycaemia?

The body’s most important glucose sensors are located in the brain (the brainstem and hypothalamus), with 30% of blood glucose being used to sustain normal brain activity (Amiel 2021).

When the brain is starved of energy, it will start to shut down certain areas that control memory and balance and stimulate hunger. The brain will also release stress hormones. Following treatment of a hypo, it can take 40 minutes to re-establish full brain function.

It’s crucial to treat hypoglycaemia quickly in order to prevent the person’s BGL from continuing to decrease, which can cause them to become seriously unwell (Diabetes Australia 2024).

It’s also important to be aware that not all people with diabetes can experience hypoglycaemia. Those treated with either insulin or sulfonylurea tablets (gliclazide, glimepiride, glipizide, glibenclamide) are at risk of hypoglycaemia. The remaining glucose-lowering medicines do not cause hypoglycaemia.

How Serious is Hypoglycaemia?

Hypoglycaemia is a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality. In US hospitals, admission trends between 1999 to 2011 showed a reduction in hyperglycaemia presentations but an increase in hypoglycaemia (Lipska et al. 2014).

English hospital admission data for hypoglycaemia between 2005 and 2014 shows that 72% (72,568 admissions) occurred in people aged 60 years or older, whilst nearly one in five people had more than one admission during this nine-year period (Zaccardi et al. 2016).

Hypoglycaemia can be classified into 3 levels:

| Glycaemic criteria/description | |

| Level 1 | BGL < 3.9 mmol/L |

| Level 2 | BGL < 3.0 mmol/L |

| Level 3 | A severe event characterised by altered mental and/or physical status requiring assistance for treatment. |

(ADA 2021)

The fear and anticipation of hypoglycaemia impacts the self-management of a person with diabetes and often prevents them from achieving optimal glycaemic control. Amiel (2021) explains that for people with diabetes, hypoglycaemia may be better defined by the degree of distress and disruption each episode causes, ranging from ingesting carbohydrate when not wishing to do so, to the acute stress response symptoms, and in some cases, confusion and coma.

What Causes Hypoglycaemia?

Hypoglycaemia risk can be divided into key areas for people with diabetes who are prescribed either insulin or a sulfonylurea agent:

Medical issues:

- Strict glycaemic control

- Previous history of severe hypos

- Long duration of type 1 diabetes

- Lipohypertrophy at injection sites

- Impaired hypo awareness

- Severe hepatic dysfunction

- Heart failure

- Adrenal insufficiency

- Impaired renal function and dialysis

- Terminal illness

- Cognitive dysfunction/dementia.

Lifestyle issues:

- Increased exercise (relative to usual)

- Rehabilitation programs

- Alcohol

- Increasing age

- Early pregnancy

- Breastfeeding

- Lack of or inadequate blood glucose monitoring

- Religious fasting

- Weight loss.

Carbohydrate intake issues:

- Reduced carbohydrate intake/absorption

- Food malabsorption i.e. gastroenteritis

- Coeliac disease

- Bariatric surgery.

(JBDS-IP 2023)

For inpatients with diabetes, hypoglycaemia risks can be significant and may include:

Insulin prescription errors:

- Inappropriate use of ‘stat’ or PRN rapid/short-acting insulin

- Confusion about insulin name, dose, concentration etc.

- Misreading poorly written prescriptions

- Inaccurate medication history and failure to perform medication reconciliation upon admission.

Medical issues:

- Incorrect type of insulin or glucose-lowering medication prescribed and administered

- Change of insulin administration site

- Intravenous insulin with or without glucose infusion

- Failure to monitor BGLs adequately whilst intravenous insulin infusion is in situ

- Inadequate mixing of intermediate or pre-mixed insulins

- Sudden discontinuation of long-term corticosteroids

- Recovery from acute illness or stress

- Mobilisation after illness

- Major limb amputation.

Carbohydrate intake issues:

- Missed or delayed meals

- Less carbohydrate than normal

- Change in the timing of the biggest meal of the day

- Lack of access to usual between-meal or bedtime snacks

- Prolonged starvation or fasting time

- Vomiting

- Reduced appetite.

Enteral/parenteral feeding issues:

- Blocked/displaced tube

- Change in feed regimen

- Discontinuation of enteral feed

- Discontinuation of TPN or IV glucose

- Insulin or sulfonylurea medicines administered at an inappropriate time to feed regimen

- Feed intolerance.

(JBDS-IP 2023)

When people who have diabetes use the same spot to inject insulin, they can develop fibrous and hardened areas. Therefore, the insulin does not get absorbed from that site, causing the patient to increase their dose. If the patient then administers that higher dose of insulin in a non-affected area, they are at risk of a severe hypo, because they are absorbing 100% of that insulin, as opposed to injecting it into the affected areas of lipohypertrophy.

Those with impaired renal function, including patients on haemodialysis, will have an increased hypo risk. This is because people need less insulin once they’re on dialysis. Furthermore, as the kidneys (or renal function) deteriorate, they are unable to remove the byproducts of these medicines.

Individuals with chronic kidney disease, heart failure and/or cardiovascular disease have a higher rate of severe hypos than those without comorbidity.

Hypoglycaemia in People with Type 1 Diabetes

People with type 1 diabetes experience around two episodes of mild hypoglycaemia every week. The annual prevalence of severe hypos in people with type 1 diabetes is close to 30%. Factors such as how long the person has had the condition may increase their risk.

People with type 1 diabetes are highly likely to have a hypo (83%). 40% of those people will experience hypos at night and 15% of these cases will be deemed severe (Frier 2014).

Hypoglycaemia in People with Type 2 Diabetes

Adults with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes experience a lower frequency of mild and severe hypoglycaemia episodes compared to those with type 1. However, the frequency of those hypos rises progressively the longer they are treated with insulin (Frier 2014).

In people with type 2 diabetes, less than half will experience a hypo over a month. Only 15% will experience them at night, and a much lower number (8%) will experience a severe hypo.

Patients with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes are more likely to require hospital admission for a severe hypoglycaemic episode compared to those with type 1 diabetes (Frier 2014).

Signs and Symptoms of Hypoglycaemia

| Autonomic symptoms | Neuroglycopenic symptoms |

|---|---|

|

|

(Tauchmann 2024)

In addition, headache (especially frontal) and nausea can also be experienced.

Management of Hypoglycaemia

Treatment of hypoglycaemia will depend on four factors:

- Is the patient conscious and cooperative?

- Is the patient on an insulin infusion?

- Is the patient nil by mouth or nil by tube?

- Is the patient receiving food orally or by tube?

It is vital to remember that you are treating low blood glucose, not low blood sugar. According to the American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care (2021), hypoglycaemic treatment with pure glucose is the preferred option as it correlates with a quicker response compared to carbohydrate foods.

The first step is to check the blood glucose level. Following this, the treatment is always the same: replace low blood glucose with glucose. Hypoglycaemia treatment is outlined on the National Subcutaneous Insulin Chart and the National Subcutaneous Non-Acute Insulin Chart (ACSQHC 2022).

The ‘Rule of 15’ effectively treats hypoglycaemia. It involves 15 grams of glucose, which is available in various forms.

If BGL is under 4 mmol/L and the patient is receiving food orally or by tube:

Step 1: Preferred treatment: Consume 15 grams of glucose. Examples include:

- Four large glucose jellybeans

- 100 ml Lucozade

- One tube of oral glucose gel (now available in a variety of flavours)

- Glucose tablets or glucose chews equivalent to 15 grams of carbohydrate (now available in a variety of flavours).

In the absence of available glucose, consume 15 grams of fast-acting carbohydrate. Examples include:

- 150 ml regular (non-diet) soft drink

- Three teaspoons of sugar or honey

- 125 ml fruit juice

- Note: Chocolate is no longer recommended due to its high fat content, which slows down the absorption of carbohydrates.

Wait 15 minutes and then check BGL.

Step 2: If BGL is still 4.0 mmol/L or less, repeat step 1 (or step 2 if glucose is not available) and recheck blood glucose in 15 minutes.

Step 3: If BGL has increased to above 4 mmol/L, consume a nutritious meal to maintain BGL.

If the next meal is more than an hour away, consume a snack containing 15 grams of longer-acting carbohydrate. Examples of snacks include:

- One slice of bread

- One glass of milk

- One piece of fruit

- Two to three pieces of dried apricots, figs or other dried fruit

- One tablespoon of sultanas

- One tub of natural low-fat yoghurt.

(NDSS 2022; JBDS-IP 2023; Better Health Channel 2021; CDC 2024)

For patients prescribed a thickened fluid/vitamised diet, initial hypoglycaemia treatment requires one tube of oral glucose gel that can be squeezed onto a spoon for ease of use. The use of thickened cordial or adding sugar to vitamised food will delay the initial reversal of hypoglycaemia. If BGL has risen above 4.0 mmol/L, the patient should consume a meal or a 15 g snack (if their next meal is more than an hour away) within 15-20 minutes. Ensure the meal or snack is appropriately prepared in line with the patient’s texture modification requirements (Better Health Channel 2021).

For patients on enteral tube feeding, initial treatment of 15 g glucose powder administered by the tube and flushed with 40 to 50 ml to prevent tube blockage should be administered. If BGL has risen above 4.0 mmol/L, commence the next feed within 15 to 20 minutes.

If BGL is under 4 mmol/L and the patient is nil by mouth or nil by tube:

- Contact the doctor urgently and if IV access is in situ, administer 30 ml 50% glucose as a slow IV push. If no IV access, administer 1 mg glucagon IM.

- Commence or revise IV glucose infusion.

- Recheck BGLs in 15 minutes.

- If BGL remains < 4.0 mmol/L, repeat initial treatment. If BGL is > 4.0 mmol/L, follow up with oral carbohydrate or IV glucose.

If BGL is under 4 mmol/L and the patient is on an insulin infusion:

- Stop insulin infusion, continue glucose infusion and contact the doctor urgently.

- If the patient is nil by mouth, administer 30 ml 50% glucose as a slow IV push. If the patient is not nil by mouth, implement usual oral hypo treatment.

- Recheck BGL in 15 minutes.

- If BGL < 4.0mmol/L, repeat initial treatment. If BGL > 4.0 mmol/L, revise insulin infusion rate and concurrent glucose infusion.

- Recommence insulin infusion and glucose infusion at adjusted rate for 15 minutes after the hypoglycaemic event has resolved.

If BGL is under 4 mmol/L and the patient is not conscious or cooperative, is drowsy or is unable to swallow in a subacute setting:

- Place the person on their side, ensuring their airway is clear.

- Administer 1 mg glucagon IM if available and trained to do so.

- Call the ambulance on triple zero (000) and state ‘diabetic emergency’.

- Stay with the person and monitor airway and cardiac status.

- Notify the treating doctor.

- If the patient regains consciousness before the ambulance arrives, give 15 g of fast-acting carbohydrate.

- Recheck BGL and if < 4.0 mmol/L and safe to do so, give another 15 g of fast-acting carbohydrate.

- Repeat BGL checks every 15 minutes until the ambulance arrives.

The Impacts of Hypoglycaemia

A cumulative impact of hypoglycaemia exists that can include:

Societal impacts:

- Loss of driving privileges

- Restricted employment

- Breakdown of family relationships and restricted access to children

- Carer stress and burden

- Additional home based resources/services or relocation to residential care.

Economic impacts:

- Additional medical care costs

- Time lost from work

- Costs of accidents (road/workplace) occurring as a result of hypoglycaemia.

Impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia:

- Occurring as a result of recurrent hypoglycaemia.

Future mortality:

- Severe hypoglycaemia is estimated to be associated with an increased future mortality risk of 50 to 600%.

Cognitive function:

- Recurrent hypoglycaemia in children may have a lasting impact on cognition as adults

- There is a relationship between dementia and hypoglycaemia in older adults with diabetes.

(Amiel 2021)

It’s helpful and useful to acknowledge the fears and concerns people with diabetes have towards hypoglycaemia. Self-management behaviour can change as a result, for example, suboptimal dosing of insulin, overeating and avoiding social situations or sporting activities.

Resources are available through the National Diabetes Services Scheme.

Reducing the Risk of Hypoglycaemia

Wearable technology such as continuous glucose monitoring with alarm alerts for low blood glucose levels has significantly reduced the number of hypoglycaemic events by notifying when blood glucose levels reach a specified level.

Smart insulin pumps and hybrid closed-loop systems also reduce the time spent in a hypoglycaemic range. With the future development of full closed-loop systems, technology will adapt to the individual's changing insulin demands, taking into account meals, exercise, emotions and stress (Mathieu 2021).

The future may include ‘smart’ insulin that is activated/deactivated depending on ambient glucose levels, thus eliminating the risk of hypoglycaemia.

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

Which one of the following is considered a severe event in hypoglycaemia management (Level 3)?

Topics

References

- American Diabetes Association 2021, ‘6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021’, Diabetes Care, vol. 44, supp. 1, S73–S84, viewed 20 August 2024, https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/44/Supplement_1/S73/30909/6-Glycemic-Targets-Standards-of-Medical-Care-in

- Amiel, SA 2021, ‘The Consequences of Hypoglycaemia’, Diabetologia, vol. 64, pp. 963-970, viewed 20 August 2024, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00125-020-05366-3

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2022, National Subcutaneous Insulin Medication Charts, Australian Government, viewed 20 August 2024, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/medication-safety/medication-charts/national-standard-medication-charts/national-subcutaneous-insulin-medication-charts

- Better Health Channel 2021, Hypoglycaemia, Victoria State Government, viewed 20 August 2024, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/hypoglycaemia

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2024, Treatment of Low Blood Sugar (Hypoglycemia), U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, viewed 20 August 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/low-blood-sugar-treatment.html

- Diabetes Australia 2024, Hypoglycaemia (Hypo) and Hyperglycaemia, Diabetes Australia, viewed 20 August 2024, https://www.diabetesaustralia.com.au/living-with-diabetes/managing-your-diabetes/hypoglycaemia/

- Frier, BM 2014, ‘Hypoglycaemia in Diabetes Mellitus: Epidemiology and Clinical Implications’, Nature Reviews Endocrinology, vol. 10, no. 12, pp. 711-722, viewed 20 August 2024, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25287289/

- Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care 2023, The Hospital Management of Hypoglycaemia in Adults with Diabetes Mellitus, JBDS-IP, viewed 20 August 2024, https://diabetes-resources-production.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/resources-s3/public/2023-03/JBDS%2001%20Hypo%20Guideline%20with%20qr%20code.pdf

- Lipska, KJ, Ross, JS & Wang, Y 2014, ‘National Trends in US Hospital Admissions for Hyperglycemia and Hypoglycemia Among Medicare Beneficiaries, 1999 to 2011’, JAMA Intern Med., vol. 174, no. 17, pp. 1116-1124, viewed 20 August 2024, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/article-abstract/1871566

- Mathieu, C 2021, ‘Minimising Hypoglycaemia in the Real Work: The Challenge of Insulin’, Diabetologia, vol. 64, pp. 978-984, viewed 20 August 2024, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00125-020-05354-7

- National Diabetes Services Scheme 2022, Managing Hypoglycaemia, Diabetes Australia, viewed 20 August 2024, https://www.ndss.com.au/wp-content/uploads/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-managing-hypoglycaemia.pdf

- Tauchmann, P 2024, ‘Diabetes Emergencies: Hypoglycaemia’, Ausmed, 30 July, viewed 20 August 2024, https://www.ausmed.com.au/cpd/courses/diabetes-hypoglycaemia

- Zaccardi F et al. 2016, ‘Trends in Hospital Admissions for Hypoglycaemia in England: A Retrospective, Observational Study’, The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology, vol. 4, no. 8, pp. 677-685, viewed 20 August 2024, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landia/article/PIIS2213-8587(16)30091-2/fulltext

New

New