Perineal tears, while common and usually minor, may cause significant complications if the injury is extensive.

What is a Perineal Tear?

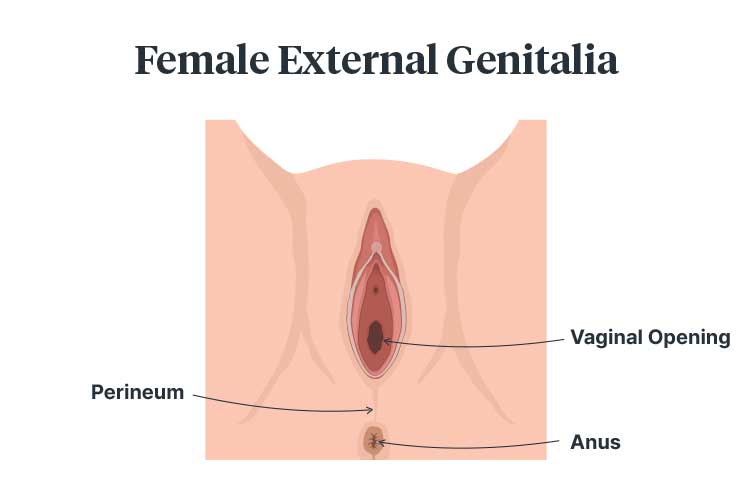

A perineal tear occurs when the perineum - the area between the vagina and anus - is injured during childbirth (ACSQHC 2021).

Tears are caused by the fetal head stretching the vagina and perineum during delivery (RCOG 2019a).

While perineal tears are common, occurring in over 85% of vaginal births (Goh et al. 2018), most do not result in serious injury (ACSQHC 2021).

However, third and fourth degree perineal tears (also known as severe perineal tears or obstetric anal sphincter injuries), which are experienced by approximately 3% of people giving birth vaginally and 5% of people giving birth vaginally for the first time, are more serious and may lead to complications (ACSQHC 2021).

Third and fourth degree perineal tears may adversely affect physical, psychological and sexual wellbeing, and sometimes require surgery (ACSQHC 2021).

While it is possible to reduce the risk of experiencing a perineal tear, they are not completely preventable. However, with effective treatment, including specialised care (if required), most patients who experience tears are able to recover (ACSQHC 2021).

Perineal Tear Risk Factors

There are three categories of risk factors for perineal tears: maternal, fetal, and intrapartum (Goh et al. 2018).

Maternal risk factors include:

- Giving birth for the first time

- Being of South Asian descent

- Being 20 years of age or under

- Vaginal birth after a previous caesarean section

- Short perineal length (less than 2.5 cm from the posterior fourchette to the mid-anus)

- Having previously experienced a severe perineal tear.

(ACSQHC 2021; Goh et al. 2018)

Fetal risk factors include:

- Birth weight of over 3.5 to 4 kg

- Being in the occipito-posterior position for a prolonged amount of time

- Shoulder dystocia.

(ACSQHC 2021)

Intrapartum risk factors include:

- Instrumental vaginal delivery (e.g. using forceps or vacuum)

- Prolonged second stage of labour (more than 60 minutes)

- Undergoing an epidural

- Undergoing labour induction

- Undergoing labour augmentation

- Undergoing midline episiotomy

- Being given oxytocin

- Being in certain birthing positions (supine, lithotomy, or deep-squatting).

(ACSQHC 2021; Goh et al. 2018)

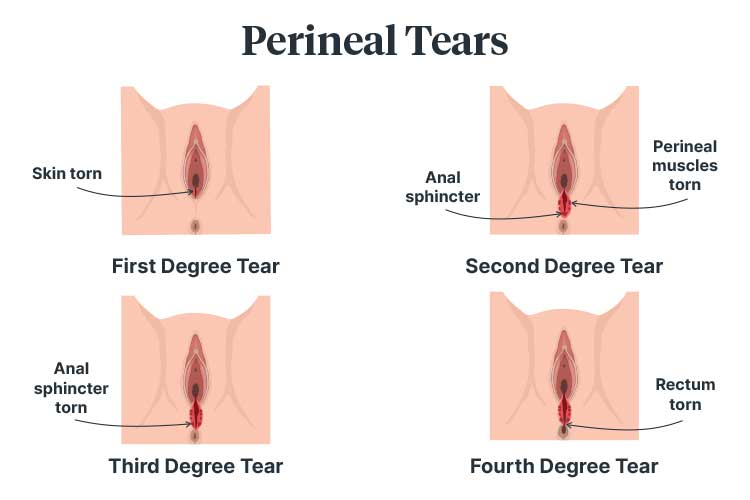

Perineal Tear Classification

Perineal tears are classified depending on the extent of the injury, with first degree tears being the most minor and fourth degree tears being the most severe (Queensland Health 2021a).

| Degree | Description | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A shallow injury that affects the skin only of the vaginal mucosa or perineum. | May heal on its own or require stitches. Recovery is usually within the first few weeks or months after birth. | |

| 2 | An injury that affects the perineal muscles. | Usually requires stitches. Recovery is usually within the first few weeks or months after birth. | |

| 3 | An injury that affects the perineal muscles and anal sphincter muscles. There are three sub-classifications: | Usually requires stitches given in an operating theatre under anesthetic. | |

| 3A | Less than 50% of the external anal sphincter is injured. | ||

| 3B | More than 50% of the external anal sphincter is injured. | ||

| 3C | Both the external and internal anal sphincters are injured. | ||

| 4 | An injury to the perineum that extends through the anal sphincter to the anal epithelium. | Usually requires stitches given in an operating theatre under anesthetic. |

(Goh et al. 2018; Queensland Health 2021a, b; RCOG 2019b)

Consequences of Severe Perineal Tears

Those who experience third and fourth degree perineal tears may experience short-term or long-term adverse effects including:

- Perineal pain

- Infection

- Incontinence (faecal and flatus)

- Pain during sexual intercourse

- Impaired quality of life

- Depression

- Impaired bonding between the parent and child due to pain and suturing time

- Psychological distress and social isolation.

(ACSQHC 2021; Ramar & Grimes 2023)

What is an Episiotomy?

An episiotomy involves making an incision in the perineum to increase the diameter of the vaginal opening. This creates more space for the fetal head, reducing the risk of a third or fourth degree perineal tear (ACSQHC 2021; Goh et al. 2018).

The incision made in an episiotomy is similar to a second degree perineal tear (Queensland Health 2021a).

An episiotomy should be performed using a medio-lateral technique with an incision angle of 60° from the midline (ACSQHC 2021).

An episiotomy is indicated in the following situations:

- There is a high risk of third or fourth degree perineal tear

- Shoulder dystocia

- The fetus is compromised and requires accelerated delivery

- The patient has a history of female genital mutilation.

(ACSQHC 2021)

With the above situations as exceptions, the routine use of episiotomy is not recommended (SCV 2019).

Repairing Perineal Tears

Perineal tears are usually repaired using stitches, with third and fourth degree tears being repaired in an operating theatre under anaesthetic (as this facilitates anal sphincter relaxation) (Goh et al. 2018).

When a perineal tear is being repaired:

- The procedure should be performed as soon as possible in order to reduce the risk of infection and blood loss

- The procedure should be performed by an experienced clinician

- The procedure should be performed in a clean, suitable environment with adequate lighting and access to equipment

- An adequate amount of anesthesia should be administered

- Each layer of the injury should be repaired independently

- The repair should be performed in a cephalocaudal direction (from the top down) to ensure access to superior sites

- The rectum should be assessed after repair to ensure sutures have not been inserted through the anorectal mucosa

- The sutures used should be resorbable. The knots of each layer should be buried to reduce the risk of postoperative dyspareunia and vaginal discomfort.

(Goh et al. 2018; ACSQHC 2021)

Postoperative Management Following the Repair of Perineal Tears

This may include:

- Antibiotics to reduce the risk of infection or wound dehiscence

- Analgesia:

- Topical cold packs used at 10 to 20-minute intervals for the first 24 to 72 hours after surgery

- Paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Urinary alkalinisers

- Urinary catheterisation

- Laxatives to reduce the risk of wound dehiscence

- Stool softeners for the first 10 days after surgery

- Positioning to reduce perineal oedema for the first 48 hours after surgery (lying on a flatbed while resting, lying on the side while breastfeeding and avoiding being seated too often)

- Avoiding activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure for the first 6 to 12 months after birth

- Commencing pelvic floor exercises two to three days postoperatively (or when the patient feels comfortable enough to do so)

- Referral to a physiotherapist who specialises in perineology

- Wound care (washing and patting the wound dry after toileting, inspecting the wound daily, using a washer instead of toilet paper).

(Goh et al. 2018; ACSQHC 2021)

Following repair, the patient may need to be referred to an obstetrician if they are experiencing:

- Wound dehiscence

- Severe pain during sexual intercourse

- Constipation

- Excessive straining

- A feeling of incomplete emptying

- A feeling of obstruction

- Digitation

- Faecal incontinence

- Urge incontinence

- Passive or post-defecation incontinence.

(Goh et al. 2018)

Reducing the Risk of Perineal Tears

Strategies to reduce the risk of experiencing a perineal tear include:

- Massaging the perineum during late pregnancy (after 34 weeks)

- Pelvic floor muscle exercises

- Regular exercise and eating a healthy diet to maintain a healthy maternal and fetal weight.

(Queensland Health 2021a; ACSQHC 2021)

During labour and birth, strategies include:

- Giving birth in certain positions (lying on one side, kneeling, standing or being on hands and knees)

- While pushing, avoiding squatting, sitting, or using a birth stool for prolonged periods of time

- Having a warm compress on the perineum during the second stage of labour

- Pushing in a slow and controlled way and listening to the midwife and doctor

- Perineal massage by the midwife during the second stage of labour

- Reducing the speed at which the neonate's head and shoulders emerge.

(Queensland Health 2021a; ACSQHC 2021)

Third and Fourth Degree Perineal Tears Clinical Care Standard

The Third and Fourth Degree Perineal Tears Clinical Care Standard was released by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care in 2021.

This standard aims to decrease unwarranted clinical variation in cases of third and fourth degree perineal tears and ensure patients who have experienced third or fourth degree perineal tears receive appropriate care that enhances physical and psychological recovery.

The standard comprises the following seven Quality Statements:

| Quality Statement 1: Information, shared decision making and informed consent | Patients are appropriately informed about the possibility of experiencing a third or fourth degree perineal tear by the third trimester. This information is individualised and provided to the patient in a way they can understand. |

| Quality Statement 2: Reducing risk during pregnancy, labour and birth | During pregnancy, patients are advised on how to reduce the risk of a severe tear. During labour, the clinician uses evidence-based strategies to reduce the risk. |

| Quality Statement 3: Instrumental vaginal birth | When an instrumental delivery is indicated, the clinician considers clinical need and the potential benefits and risks (including the risk of a severe perineal tear). |

| Quality Statement 4: Identifying third and fourth degree perineal tears | Patients are examined after vaginal birth for perineal tears by an appropriately qualified clinician. Any identified tears are appropriately classified and documented. |

| Quality Statement 5: Repairing third and fourth degree perineal tears | Third and fourth degree tears are quickly repaired in an appropriate environment by an appropriately qualified clinician. |

| Quality Statement 6: Postoperative care | Patients receive postoperative care after repair of a severe tear. This should comprise debriefing, physiotherapy and psychosocial support. |

| Quality Statement 7: Follow-up care post-discharge | Patients receive individualised follow-up care after repair of a severe tear to optimise physical, emotional, psychological and sexual health. They are referred to a specialist if required. |

(ACSQHC 2021)

Topics

References

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2021, Third and Fourth Degree Perineal Tears Clinical Care Standard, Australian Government, viewed 8 February 2024, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/third-and-fourth-degree-perineal-tears-clinical-care-standard-2021

- Goh, R, Goh, D & Ellepola, H 2018, ‘Perineal Tears – A Review’, Australian Journal of General Practice, vol. 47, no. 1-2, viewed 8 February 2024, https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2018/january-february/perineal-tears-a-review

- Queensland Health 2021a, Perineal Tears, Queensland Government, viewed 8 February 2024, https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/142197/c-peritears.pdf

- Queensland Health 2021b, Third and Fourth Degree Perineal Tears, Queensland Government, viewed 8 February 2024, https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/150363/c-peritears-34degree.pdf

- Ramar, CN & Grimes, WR 2023, ‘Perineal Lacerations’, StatPearls, viewed 8 February 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559068/

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2019a, Perineal Tears During Childbirth, RCOG, viewed 8 February 2024, https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/patients/tears/tears-childbirth/

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2019b, Third- and Fourth-Degree Tears (OASI), RCOG, viewed 8 February 2024, https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/patients/tears/third-fourth/

- Safer Care Victoria 2019, Care During Labour and Birth, Victoria State Government, viewed 12 February 2024, https://www.safercare.vic.gov.au/best-practice-improvement/clinical-guidance/maternity/care-during-labour-and-birth

New

New