What is Polycystic Kidney Disease?

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a predominantly genetic condition causing cysts (fluid-filled blisters) to grow on the kidneys (Better Health Channel 2022).

These cysts gradually enlarge the kidneys as they grow, causing healthy kidney tissue to be compressed. Eventually, this impairs kidney function and, in some cases, leads to kidney failure (Better Health Channel 2022; Kidney Health Australia 2019).

Both kidneys are affected, but one might progress earlier than the other (Kidney Health Australia 2019).

As well as in the kidneys, cysts may also grow in other organs, including the liver, pancreas, spleen, ovaries, large bowel, heart and brain (NKF 2025).

What Causes Polycystic Kidney Disease?

PKD occurs due to a mutation in the PKD1, PKD2 or PKHD1 gene (Better Health Channel 2017).

This mutation is believed to cause increased cell growth, which leads to the formation of cysts (Bennett et al. 2024).

In most cases, the mutation is inherited, however, it’s also possible for PKD to occur in someone with no family history of the illness. This is thought to be caused by a spontaneous gene mutation (Mayo Clinic 2024).

There are two inheritance patterns of PKD:

- Autosomal dominant (ADPKD)

- Autosomal recessive (ARPKD).

(Kidney Health Australia 2019)

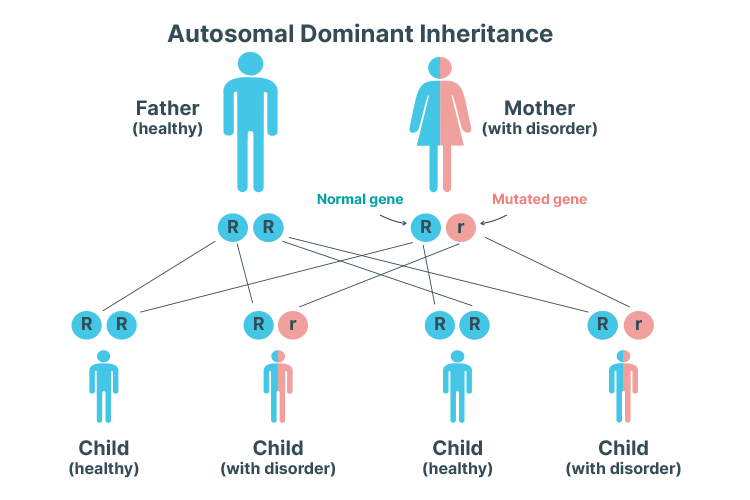

Autosomal Dominant PKD

ADPKD is the most common type of PKD (Kidney Health Australia 2019).

In ADPKD, cysts begin to form during childhood but are initially microscopic and impossible to detect until later in life. Symptoms don’t typically develop until between 30 and 40 years of age (Kidney Health Australia 2019).

An autosomal dominant inheritance pattern means that only one copy of the mutated gene is needed to cause PKD. In other words, a child has a 50% chance of inheriting PKD if one of their parents has the mutated gene (Mayo Clinic 2024).

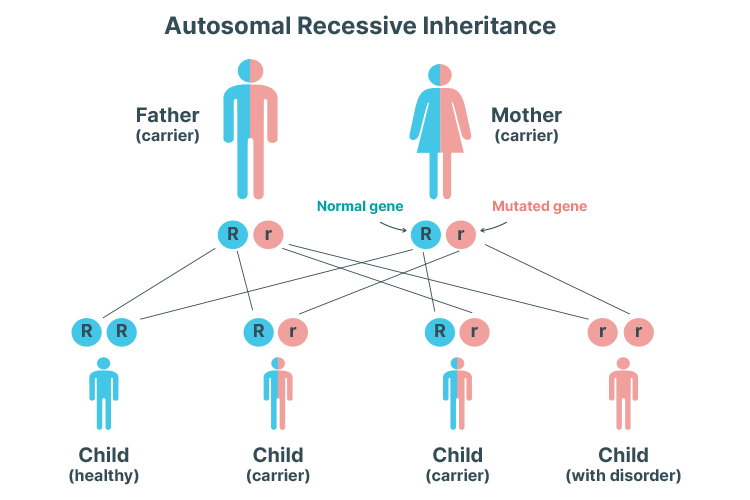

Autosomal Recessive PKD

ARPKD is much less common. Unlike ARPKD, symptoms typically begin to develop during early childhood, or in some cases, as early as in the womb (Better Health Channel 2022).

ARPKD can cause kidney and/or liver problems later in the patient’s life (Kidney Health Australia 2019).

An autosomal recessive inheritance pattern means that two copies of the mutated gene are needed to cause PKD. In other words, the condition can only be inherited if both parents are carrying the mutated gene and the child inherits one mutated gene from each parent. One mutated gene is not enough to cause PKD alone - instead, the child will become an asymptomatic carrier. The likelihood of inheriting two copies of the mutated gene is 25% (Mayo Clinic 2024).

Symptoms of Polycystic Kidney Disease

Autosomal Dominant PKD

People with ADPKD don’t usually present with symptoms in early life, but between the ages of 30 and 40 (on average), they may begin to experience:

- Polyuria (needing to urinate more often)

- Nocturia (needing to urinate during the night)

- Kidney pain

- Haematuria (blood in urine)

- Hypertension

- Impaired kidney function or kidney failure

- Enlarged, painful abdomen

- Urinary tract infections

- Kidney stones

- Hernias

- Cysts in other organs (often the liver)

- Mitral valve prolapse (caused by cysts in the heart), which may lead to a heart murmur

- Intracranial aneurysm (caused by cysts in the brain), which can lead to a stroke or even death.

(Kidney Health Australia 2019; NKF 2025)

About 50% of people with ADPKD will experience kidney failure by the age of 60 (Kidney Health Australia 2019).

Autosomal Recessive PKD

Symptoms of ARPKD may include:

- Unusually-shaped face (due to a lack of fluid surrounding the fetus in the uterus)

- Delayed or difficult childbirth

- Hypertension

- Swollen abdomen caused by enlarged kidneys, liver and spleen

- Heart or lung defects

- Kidney failure at birth or in the first few weeks of life

- Failure to thrive

- High blood pressure in the liver

- Haematuria

- Hypertension

- Anaemia.

(Kidney Health Australia 2019)

Diagnosis of Polycystic Kidney Disease

Autosomal recessive PKD can usually be diagnosed early due to patients commonly presenting with severe symptoms at a young age (Kidney Health Australia 2019).

Autosomal dominant PKD, on the other hand, may go unnoticed for many years and is often detected during investigations for other health issues (e.g. urinary tract infection). Some people with ADPKD aren’t diagnosed until their kidneys begin to fail (Better Health Channel 2022).

Diagnosis of PKD will take into consideration the patient’s age, as well as any family history of the condition (Kidney Health Australia 2019).

The most reliable, cost-effective and non-invasive method of detecting cysts is via an ultrasound (NKF 2018).

If cysts are detected, further diagnostic tests might be performed, including:

- Physical examination to detect hypertension or enlarged kidneys

- Blood tests to check kidney function

- Urine tests to assess for haematuria and proteinuria (protein in urine).

(Kidney Health Australia 2019)

Genetic testing might be used in some cases, but it isn’t a routine diagnostic method as it is costly and not always accurate (NKF 2025).

PKD will be diagnosed in at-risk people with a family history of the condition if:

| Patient age | Number of cysts found on ultrasound |

|---|---|

| 15-39 years | At least 3 (in total) |

| 40-59 years | At least 2 in each kidney |

| < 60 years | At least 4 in each kidney |

(Kidney Health Australia 2019)

Treatment for Polycystic Kidney Disease

There is no cure for PKD, but early detection and management can help to reduce the risk of complications (Better Health Channel 2017).

Typically, first-line treatment involves slowing the growth of cysts via lifestyle management and modification (e.g. regular exercise, smoking cessation, dietary changes), along with controlling blood pressure. In some cases, these are the only interventions needed (Kidney Health Australia 2019).

Other interventions may include:

- Antihypertensive medicines

- Draining cysts to relieve pain

- Fluids, analgesia, antibiotics and rest to treat haematuria

- Antibiotic treatment for any urinary tract infections

- Medicine to slow the progression of cysts (for adults with rapidly progressing ADPKD)

- Dialysis or a kidney transplant to treat kidney failure

- Psychological support to help manage feelings of sadness and anxiety associated with a PKD diagnosis

- Avoiding contact sports if the kidneys, liver, spleen or abdomen are enlarged, as these organs could potentially be injured if hit.

(Kidney Health Australia 2019; Better Health Channel 2022)

Patients should also be advised to avoid taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as they can potentially worsen kidney function (Better Health Channel 2022).

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

Which type of polycystic kidney disease is more common?

Topics

References

- Bennett, WM, Rahbari-Oskoui, FF & Chapman, AB 2024, Patient Education: Polycystic Kidney Disease (Beyond the Basics), UpToDate, viewed 21 May 2025, https://www.uptodate.com/contents/polycystic-kidney-disease-beyond-the-basics

- Better Health Channel 2022, Kidneys - Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD), Victoria State Government, viewed 21 May 2025, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/kidneys-polycystic-kidney-disease-pkd

- Kidney Health Australia 2019, Polycystic Kidney Disease, Kidney Health Australia, viewed 21 May 2025, https://kidney.org.au/uploads/resources/KHA-Factsheet-polycystic-kidney-disease-2019.pdf

- Mahboob, M, Rout, P, Leslie, SW & Bokhari, SRA 2024, ‘Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease’, StatPearls, viewed 21 May 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532934/

- Mayo Clinic 2024, Polycystic Kidney Disease, Mayo Clinic, viewed 21 May 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/polycystic-kidney-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20352820

- National Kidney Foundation 2018, Polycystic Kidney Disease, NKF, viewed 21 May 2025, https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/polycystic

New

New